From our January 2003 issue.

One day recently, when Richard Moriarty, pediatrician and founder of the poison center at Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, took his money clip out of his pocket, he got an ear-beating from the grocery clerk. That’s Mr. Yuk, she said, recognizing the redoubtable image. That should only go on things that are poisonous. Moriarty (MD ’66), a longtime Pitt associate professor of pediatrics, did his best to look remorseful. But in point of fact, he was pleased. The reproach was a sign of success. After more than 30 years, Mr. Yuk was still alerting adults and children to the dangers that lurk in everyday substances. Moriarty’s proudest achievement was intact.

Time was when round green faces, with tongues stuck out in a universal sign of distaste, could not be found under the kitchen sink. Crucial information, what to do if your toddler ate a tin of shoe polish for example, wasn’t always as close as the phone. When the first poison center was established in 1953 at the behest of the American Academy of Pediatrics and funded by eight hospitals in Chicago, it was little more than an office with a part-time secretary. Each morning the secretary would call the ERs, according to William Robertson, director of the Washington Poison Center in Seattle, to “find out what kids had eaten the night before.” Then she would cajole the manufacturers into revealing the product’s ingredients. Soon, she had large index cards with the trade name and ingredients of almost a thousand items. A committee of doctors and pharmacists got together to describe the symptoms and treatments for accidental ingestions, and that information was added to the cards. Eventually, when one of the hospitals was faced with a poisoning, they would ring the secretary, and she would pass on the information. The surgeon general, Robertson recalls, heard about these cards and decided to mimeograph them to distribute cards across the country. Poison centers sprang up all over. In less than six months, the state of Illinois alone had 104 poison centers.

But index cards are easy to carry off. Before long, the information was scattered all over hospitals. The chore of actually locating all of a poison center’s cards and then keeping them current was not a task for the faint of heart.

This was the sorry state of affairs that distressed a young Moriarty, a resident at Children’s in the late 1960s. “When that number rang,” he remembers, “whoever happened to be in the emergency room suddenly was the poison center.” The illusion of expertise troubled him. So in 1971, after a fellowship in clinical pharmacology and a year as chief pediatrics resident, he took on the role of director of Children’s poison center.

Moriarty calls himself “an organizer.” He hired clerks to get the files in shape and developed a dedicated nursing staff to handle the center’s calls. One night at dinner, he mulled over the best way to share the center’s expertise with other hospitals. Should the center copy its now-efficient information base and let that suffer the same fate as the original Chicagodesigned system? Or read the information over the phone and hope nothing was misheard? The answer came in a stroke of luck—the kind that the charismatic Moriarty often seems to attract. As it happened, one of the men at the table worked for Xerox, which had an exciting new machine—a telecopier. So years and years before “fax” became an everyday word, Moriarty had telecopiers to link Presby—and soon other hospitals—to the poison center.

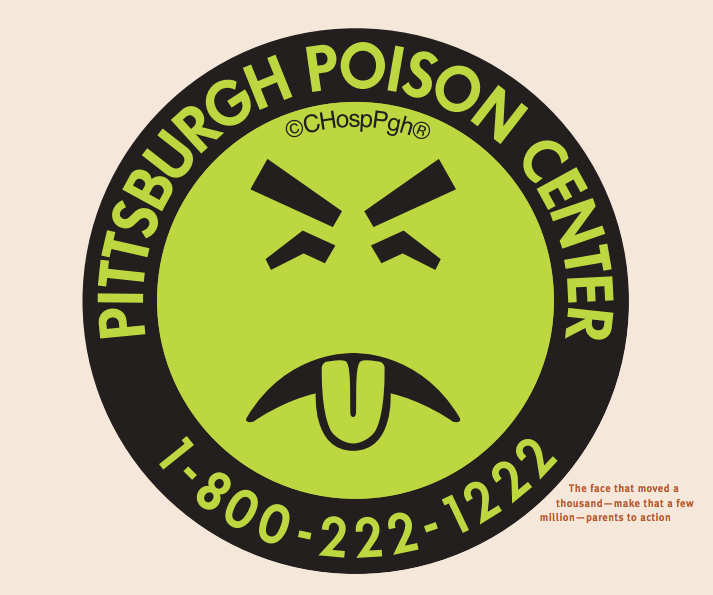

As the center at Children’s became more and more of a resource, Moriarty turned to outreach. After another dinner with friends (he didn’t eat dinner at home much in those days, he notes, laughing), Moriarty found himself hooked up with the Vic Maitland Agency and its stable of artists and advertising experts, including Dick Garber, a marketing wizard. The partnership gave birth to Mr. Yuk—one expressive little icon. (Moriarty, by the way, refers to the icon simply as “Yuk” in the comfortable way that one might refer to, say, a poker buddy or a pet.)

To come up with Yuk, the project team went directly to its audience. They asked kids: If you get into a poison, what happens? Your mother will yell at you. You’ll get sick. You’ll die—Moriarty remembers the children telling him. “So we had a yelling face. We had a sick face. We had a dead face. We went back to the kids and asked them, ‘Which one don’t you like?’ And they didn’t like the sick face.”

The finishing touch: When the artists made the sick face fluorescent green, after testing several other colors, one of the kids said, “That looks yucky.” And that was that.

Robertson still remembers the stir that Yuk created when Moriarty presented it at the national meeting of the American Association of Poison Control Centers in the mid-’70s. “[Children’s was] the first to use mass media,” Robertson says. “For a minimum amount of dollars you could influence the population in a hurry.” The Washington Poison Center was the first to sign on to the Mr. Yuk program. In a short time, 96 percent of the people in the Seattle area could identify Mr. Yuk. “It had an amazing impact,” says Robertson.

“Some of our colleagues said stickers can’t do much good to keep a 2-year-old out. Well, it’s true! The 2-year-old doesn’t pay attention. But the parents who put the sticker on learned a lesson.”

By 1978, the number of poison centers had swelled to 700. Edward Krenzelok, a Pitt professor of pediatrics as well as pharmacy and therapeutics is current director of the Pittsburgh Poison Center. (Moriarty stepped down in 1983.) He says that Moriarty was ahead of his time in developing a network of regionalized poison centers. “Dick promoted the idea that we should have a number of strong centers rather than a million little centers that weren’t necessarily meeting everybody’s needs. His was one of the very first poison centers to provide 24-hour-a-day, sevenday-a-week coverage.”

Today, the United States has 65 poison centers. Last year, Children’s filled requests for 42 million Mr. Yuk stickers and answered 82,000 poison-inquiry phone calls. In January 2002, Mr. Yuk started advertising a national number—1-800-222-1222—that routes calls to the nearest center.

Meanwhile, Moriarty still runs into parents who tell him Mr. Yuk saved their child’s life. So if every once in a while he has to endure a scolding when he pulls out his treasured money clip (a gift from former Department of Pediatrics chair Tim Oliver), so be it.

This story has been adapted into a podcast! Hear it on Pitt Medcast: