In 1958, when Louis W. Sullivan began his residency at Cornell, he was the only black intern in New York Hospital. Summoned to the office of E. Hugh Luckey, physician in chief, he went with trepidation. Luckey, a Tennessee native with a heavy Southern accent, surprised the young doctor.

In 1958, when Louis W. Sullivan began his residency at Cornell, he was the only black intern in New York Hospital. Summoned to the office of E. Hugh Luckey, physician in chief, he went with trepidation. Luckey, a Tennessee native with a heavy Southern accent, surprised the young doctor.

“Luckey … wanted to let me know he was interested in my succeeding, and that he would support me,” Sullivan said. “This gave me the assurance that there was someone there who really cared about what I was trying to do. In two years [at the hospital] I had only one negative experience. A patient objected to my examining him, and he was immediately discharged. That’s the kind of thing we need to see more of now.”

Sullivan, who served as Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services from 1989 to 1993, recalled this incident in a lecture titled “The Long Journey to Health Equity in America,” delivered on Oct. 2, 2015, to an audience of Pitt medical students, physicians, and other health care professionals. While there are still far too few minorities in the health professions, he said, we must support the ones who are there now.

In a talk rich in historical perspective and dense with data, the 82-year-old hematologist and founding dean of the Morehouse School of Medicine traced the evolution of disparities in both health and the health professions throughout the past century, citing milestones from the 1910 Flexner Report to the 2010 signing into law of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), also known as Obamacare.

Looking forward, Sullivan offered a clear set of recommendations for improving the health of the nation as a whole: increase access to health services; instill better health behaviors; streamline what is a very “bureaucratic” health care system; develop guidelines to address ethical challenges brought by technological and scientific advances; and preserve humanism in the therapeutic relationship.

In the end, Sullivan exhorted listeners to be role models in their communities. “The greatest reward in my life has been seeing young people develop as professionals and go off and do great things. Medical students represent the vitality and future of our society,” he noted.

Sullivan’s talk was the culminating event in the daylong Health Disparities Conference 2015, hosted by the Physician Inclusion Council of UPMC/Pitt. His comments were followed by a panel conversation that included Esa Davis, an MD/MPH and assistant professor of medicine; Larry Davis, a PhD, dean of the School of Social Work, and director of the Center on Race and Social Problems; and Patricia Documét, an MD/DrPH, associate professor of behavioral and community health sciences and clinical and translational science, and scientific director of Pitt’s Center for Health Equity. Jeannette South-Paul, an MD and the Andrew W. Mathieson UPMC Professor and chair of the Department of Family Medicine, moderated the discussion. Recently, Pitt Med had the opportunity to ask Sullivan a few follow-up questions.

How effective can the Affordable Care Act be in reducing health disparities if 20 states have decided not to expand Medicaid?

I think states not expanding Medicaid will have a definite adverse impact on the health of low-income citizens, which includes a large number of minorities. Those states that have expanded Medicaid have seen significant reductions in the percentage of their populations who are uninsured, and hospitals have seen reductions in the amount of uncompensated care they have to provide. We have under way a significant effort to improve the health behaviors of our citizens to prevent what can be prevented. But if you have a financial barrier to seeking care, which is the case for a lot of people who are poor or low income, you won’t be able to change your health behaviors. I think the failure to expand Medicaid is very short sighted on the part of those governors. It is walking away from what I see as a community responsibility to provide access to health care for our citizens, and one that will pay not only in humanitarian terms but in economic terms, as well: a healthier population that’s working, with reduced illness and injury and therefore less need for social support services.

What can academic health centers (AHCs) do to recruit and support a diverse clinical workforce?

I see this as a long-term effort. To expand the pipeline, AHCs need to form relationships with colleges so that students get career counseling, strong academic training, and, most important, financial planning. The cost of getting a health professional’s education is so expensive. We have a system that only upper-income students can navigate financially. Increasing diversity in the workforce requires a commitment of leadership—from the CEO on down. It should be an institution-wide priority, not simply a slogan that no one gives serious attention to.

What can AHCs do to reduce health disparities in their surrounding communities?

Too often in our country we have a great AHC sitting in an urban area with serious health problems and very little interaction between them. It would be good to have the leadership of the AHCs discuss health issues with community leaders—elected officials, city council members, ministers, teachers, presidents of associations. They are the ones who have the credibility and the trust of the people who live there. Next, there needs to be a discussion about the status of the health of the people in the community. What are the problems? What are the barriers? And then, AHCs must work with community leaders to set up the programs. A program may be good from a medical point of view, but if it’s not embraced by the community it won’t be as effective. Organizations in the community could host such programs—whether it’s a community health center or the YMCA or a church. In other words, have the programs out in the community where people live, rather than waiting for the community to come into the AHC.

Do you think the topic of health disparities is part of the larger conversation taking place in this country about race?

Yes, I do. This is my perspective. When I was in medical school and postgraduate training, the civil rights movement was very active. And the aggregate of these activities—the bus rides into Mississippi; the counter sit-ins in Greensboro, N.C.; the march in Selma—raised the consciousness of the nation to these issues. The net impact was to focus people’s attention on this and to say, “This is wrong, and we’re going to do something about this.” Now we’ve gotten away from that, and people have settled back into their zones of comfort or retreat. We need to reach out and have more positive outcomes, rather than these confrontations we’ve seen throughout the past few years.

One recent example is the University of Missouri. It seems the failing there was that the president had not responded to communications from the black students about the indignities to which they were subjected. These were not addressed, it reached a boiling point, and then [there was] the explosion. In my view, that could have been avoided if there had been some response to show that the president was working to resolve the problems. We need to have more active leadership about this.

The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that by 2044, non-Hispanic whites will be a minority. Can we increase the number of minority health professionals fast enough to keep up with that shift?

By 2044 I hope we have a lot more diversity than we have now, but I would not be surprised if we still fall short in terms of how representative the nation’s health professionals are of its population, racially and ethnically. This kind of change takes time. Becoming a health professional is a lifelong goal. So we need to reach out to youngsters who are in fourth or fifth grade; it will be 15 or 20 years before they come into the system.

We can, and should, make some other changes, too. For example, I’m working on a project right now involving dental therapists. It’s a two-year program started by the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium in 2004 to train high school graduates in primary dental care and simple extractions and fillings. This is a new model, and this is similar in some broad respects to the physician assistant and nurse practitioner programs in medicine in the early ’60s and ’70s. At that time, there was a lot of resistance from physicians. But now they’re working alongside physicians, and this helps increase access to health care. I see the health system changing dynamically so that 10 to 20 years from now, we’ll see different kinds of professionals working alongside the dentists and the doctors.

If you were Secretary today, what would you address most urgently?

I would mount a much more vigorous educational campaign about the ACA. I think one of the mistakes that [President Obama] and [Secretary Kathleen Sebelius] and others made when this legislation was passed was that they did not make an effort to inform the public about what was in the statute and what its intentions were and why it would be important to everyone. They left it to those members of Congress who were ideologically opposed to paint a very negative picture of it for the American public. This allowed suspicion and mistrust to build up. The administration has been playing catch-up ever since.

Second, when the insurance exchanges were about to become operational, back in 2013, the administration did not prepare the public. The impression given was that on October 1, they’d flip a switch, and everything would be ready. But a lot of the exchanges didn’t work. And that again gave ammunition to opponents to say, “Look, it’s not working.” The wise thing would have been to say, “[October] 1 is coming, and there may be technological glitches, and, we’ll address them.” At this juncture, what needs to happen is a strong educational effort about the features of the ACA—why it’s good, where it’s working, what to expect.

Photography by Tom Altany/CIDDE, Robyn K. Coggins contributed to this report.

WHERE OTHERS DON'T GO

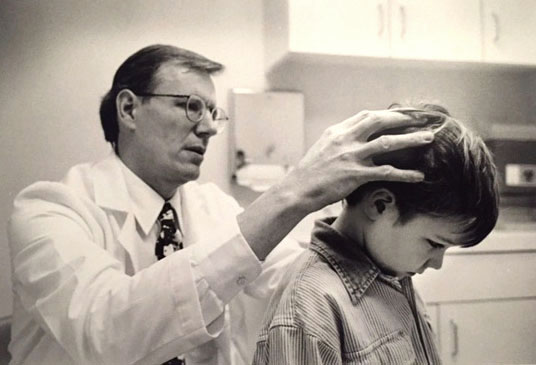

Neurosurgeon eschews familiar to bring comfort to children

BY KRISTIN BUNDY

The damage resulted from an anesthetic disaster. About 30 years earlier, during a tonsillectomy, her brain suffered a lack of oxygen that eventually changed the shape of her body. Involuntary muscle contractions—known as dystonia—distorted her into abnormal postures, causing lifelong pain.

At 35 years old, she entrusted her future to another surgical team—oddly, led by a pediatric neurosurgeon. He had treated her for years but decided to try something new, after she said a small dose of baclofen injected in her spinal fluid helped. Giving up on oral baclofen, the common but often ineffective treatment for dystonia, he implanted a pump that infuses baclofen right into the spinal fluid.

A. Leland Albright (Fel ’76, Res ’78), the pediatric neurosurgeon, didn’t know what the outcome would be, but he was known to carefully bank on educated guesses. In serious conditions for which no good solution was available, he’d adopted the approach of “try and see” (his preferred phrase over “trial and error”).

Two days after the woman’s procedure, nearly all of her symptoms were gone. “It was like she had a miracle!” Albright recalls.

Encouraged by these promising results, Albright obtained appropriate permissions from the Human Rights Committee of Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC and the National Institutes of Health and was soon at the forefront of bringing this new treatment to the clinic. The use of the baclofen pump in children suffering from dystonia and spasticity (stiff, inflexible muscles)—common disorders associated with cerebral palsy (CP)—has since benefited hundreds of children around the world.

(Albright recalls how, before this procedure, many parents of his patients with severe generalized spasticity and severe generalized dystonia would take turns waking up every couple of hours to reposition their children in the night to help them find rest. And they would do this for years.)

Albright built a career treating severe disorders that few other neurosurgeons would devote themselves to. His life is one of venturing where others don’t.

Albright’s mentor Peter Jannetta was one of the preeminent neurosurgeons of the late 20th century. Jannetta led the newly formed Department of Neurological Surgery at Pitt in the 1970s. Albright was one of his first residents. Although Albright admits he had never heard of the pediatric subspecialty when he began his residency at Children’s in 1974, he would become one of the first pediatric neurosurgeons at Pitt, following Donald Reigel and John Vries. Jannetta eventually named Albright chief, and the division soon gained esteem. (By the mid-’90s, Albright and pediatric neurosurgeon colleagues Ian Pollack and P. David Adelson became the senior editors of the book Principles and Practice of Pediatric Neurosurgery. The latest edition came out in 2014.)

Albright treated and operated on children with spina bifida, brain tumors, and head injuries, but he’s also devoted to children with disabilities for which there’s no cure. Albright explains that few physicians specialize in caring for children with movement disorders arising from brain and spinal cord abnormalities, despite the many who are disabled by these conditions.

Albright formed what’s thought to be the nation’s first multidisciplinary team to treat spasticity and movement disorders in kids. Often, children and their families would have to visit many specialists over multiple appointments at various locations. At Children’s, Albright convened all of the specialists—pediatric neurosurgeons, fellows, residents, psychiatrists, occupational and physical therapists, and nurse practitioners. They offered every known treatment for these disorders, and children came from around the country to be evaluated and treated.

“The incredibly gratifying aspect of taking care of those kids, particularly those with CP and other movement disorders,” Albright says, “is that we can make changes in their quality of life that are dramatic.”

Albright adds, “A lot of people don’t want to go into [pediatric neurosurgery] because there is so much grief. But I found it a wonderful way to express the love of God for the children and their families.”

Albright completed medical missions in several countries, including South Korea, Venezuela, and Nigeria, in his decades-long career. The culmination of those efforts came in 2010, when he and his wife, Susan Ferson, a pediatric nurse practitioner, decided to sell their house and move to Kijabe, Kenya (about an hour and a half drive from Nairobi). They’d planned to devote six years of their lives to treating children, teaching pediatric neurosurgery, and establishing a self-sustaining pediatric neurosurgery department at the Kijabe Hospital—what would become one of the first such departments in Africa.

The team came up against many barriers in Kijabe. In addition to operating with old equipment and unreliable electricity, Albright was also in the precarious position of deciding whom to treat. Thousands of families sought out the team’s care. And for most, Albright had to consider more than the disease. Would the parents be able to return the child for follow-up? Would the child die because, although the surgery might be successful, the child might not be able to receive postoperative irradiation? Could the parents afford more potent, but more costly, antibiotics? Often he and his team had to weigh the likelihood of impoverishing a whole village against providing treatment to a child.

Despite these limitations, Albright cared for more children in Kijabe per year than he was able to in the United States. Along with a Ugandan pediatric neurosurgery fellow whom Albright trained, Humphrey Okechi, Albright performed more than 5,000 operations at Kijabe Hospital in four years. The most operations he had done in a year in the States was 330.

The hours were long and the work was challenging, but, as Albright and Ferson write of their time in Kenya in a paper published in the Journal of Child Neurology, “. . . we have an inner sense of peace that we are where we should be, doing what we should be doing, and we give thanks for that. We cannot always say we enjoy it, but we love it.”

Albright had to cut his time short in Kenya after being diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (thought to be caused by a virus, not overworking). In early 2015, Albright and Ferson moved to La Grange Park, Ill., where he is now taking seminary classes to become an ordained minister through the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago.

Late last year, Albright was presented with a lifetime achievement award—the Franc D. Ingraham Award for Distinguished Service and Achievement—by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Pollack—mentee and friend of Albright’s (who’s now the A. Leland Albright Professor of Neurosurgery and division chief at Pitt)—introduced Albright during the award ceremony.

When Albright took the podium, he didn’t give a presentation on any of his clinical advances. Instead, he directly addressed the younger neurosurgeons, urging them to recognize the children who need their care, encouraging them to seek new answers and get comfortable with the uncertainty of it all.

“There are three disorders that you need to consider devoting more of your career to because nobody’s interested,” he told them. “And that’s children with serious head injuries, the 1 percent of children who have epilepsy, and the 1 out of 320 children in the U.S. that have spasticity or movement disorders.” He went on: “There are tens of thousands of children that we need to devote ourselves to.”

When he finished, several physicians approached him, ignited by his commitment to these children, seeking an exchange of ideas on how they could continue what he’d started.